WEISS: It leads to sleepless nights, trying to figure out what you haven’t thought of. You will lick it, but it’s a pain in the meantime! THORNE: It’s a standard issue that great experimenters like you and your team face. But this one is a little more troublesome, Kip! KIP THORNE: Rai, you’ve advanced through this kind of thing before many times with LIGO. We’re about a factor of three off of what should be possible, and for months now, we’ve been stuck not really understanding where a particular noise in the data is coming from. The monkey is still yacking in my ear, though, because we’re not at design sensitivity yet for LIGO. It shows what we reported in February was not a unique event and that maybe we can do gravitational wave astronomy. RAI WEISS: The second detection certainly was wonderful.

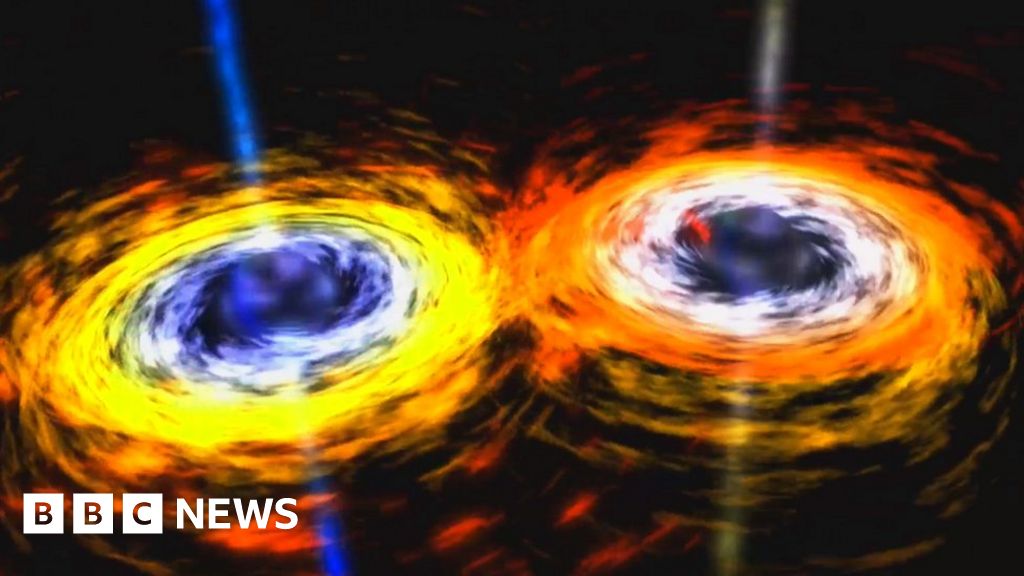

Now with the second detection made by LIGO, do you feel unburdened? Is the monkey finally out of the picture? You said you felt like a monkey had jumped off your back, but the monkey was still there, walking along on the sidewalk. After all, you had spent four decades and taken hundreds of scientists along with you on the project. Earlier this year, after the LIGO team announced the first direct detection of gravitational waves, I asked you what it felt like. The conversation has been amended and edited by the laureates. Drever was not available to participate in the conversation, due to illness. RAINER WEISS– Emeritus Professor of Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and a member of the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research.THORNE– The Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics at the California Institute of Technology. Science writer Adam Hadhazy hosted a roundtable discussion with laureates: "For the direct detection of gravitational waves," Drever, Thorne and Weiss will receive the 2016 Kavli Prize in Astrophysics. Never before had these sorts of events been discernible to science, demonstrating how LIGO has opened a whole new window on the exploration of the universe. A second detection of merging black holes followed in December 2015. LIGO made this historic detection a century after Einstein unveiled general relativity. The distinctive signature of the waves showed they had emanated from the collision of a pair of monstrous black holes, 1.3 billion light-years away. In 2015, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, registered the slightest of jolts, just one-ten-thousandth the diameter of an atomic nucleus, as passing gravitational waves locally warped space-time. Thorne and Rainer Weiss led to the development of an experiment that finally sensed gravitational waves. In the 1970s, breakthroughs by physicists Ronald W.P. Yet in the same spirit of curiosity that drove Einstein, scientists did not give up the hunt. Should any of these ripples, or gravitational waves, reach Earth, they would be so astonishingly tiny that directly measuring them looked hopeless. His general theory of relativity held that the movement of massive objects, such as black holes-another wild consequence of relativity-would create “ripples” in the fabric of space-time. One that even he thought would never be confirmed was the existence of gravitational waves. But this disappearing act can occur only if the two beams take the same amount of time to return from their journey down the two tunnels.Albert Einstein made many bold predictions. When they do that, the beams recombine and, essentially, disappear.

The beams reflect off the mirror and eventually converge back at the center. The resulting beams travel back and fourth across two tunnels, each 2 1/2 miles long, with a mirror at the end.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)